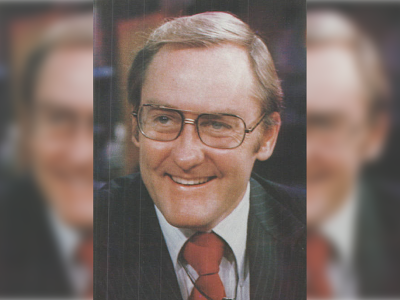

This week Illinois says goodbye to its 37th Governor, the history-making James R. Thompson. Illinois’ longest-serving governor, Thompson passed away last Friday at the age of 84.

Governor Thompson left a legacy as a builder and deal-maker. He won the biggest gubernatorial landslide in living memory as well as the closest nail-biter in Illinois history. Around the state, buildings and other projects stand today as monuments to the governorship of Jim Thompson.

Known as “Big Jim,” the six-foot-six Thompson served as Illinois Governor from 1977 until 1991. He was born on Chicago’s West Side in 1936 and went to the University of Illinois’ Chicago campus and Washington University in St. Louis, before earning his law degree from Northwestern University. Thompson became a prosecutor in the office of Cook County State’s Attorney Benjamin Adamowski, a longtime thorn in the side of the Daley political machine in Chicago. Thompson headed the appellate division of the state’s attorney’s office.

Thompson moved to the staff of Illinois Attorney General William Scott in 1969. Before long, he was a federal prosecutor in Chicago, where he made his name pursuing political corruption cases. In 1971, he was named U.S. Attorney for Northern Illinois. Corruption convictions of former Governor Otto Kerner and a series of powerful city officials, state legislators and other government employees followed.

In 1975, Thompson announced he would be a candidate for governor the following year. After feuding with the Daley machine for four years, the incumbent, Dan Walker, was defeated in the primary by Secretary of State Michael Howlett. Thompson was elected with close to 65 percent of the vote, the biggest gubernatorial win in Illinois since 1848.

Thompson brought his “tough on crime” persona to the governor’s office when he was inaugurated in 1977. He brought back Illinois’ death penalty and created the “Class X” level of felonies, enacting longer sentences for crimes such as armed robbery and attempted murder. The tougher penalties for crimes made necessary the construction of more prisons in Illinois, which would become a major state building project in the 1980s.

The Governor and the First Lady, Jayne Carr Thompson, celebrated the birth of their daughter Samantha at Memorial Hospital in Springfield in 1978. Samantha was only the second child to be born to a sitting Illinois governor. That same year, due to a change in the 1970 state Constitution, Thompson would have to stand for a second term, just two years after winning his first. He again prevailed easily, winning with 59 percent of the vote.

Thompson’s second term coincided with a nationwide recession, and the Midwest “Rust Belt” was particularly hard hit. Unemployment went up to over 11 percent in Illinois and manufacturing jobs were in steep decline. Thompson worked hard to reverse this trend, leading the effort to build overseas export markets for Illinois products and encouraging foreign companies to invest in Illinois. One of his biggest successes was the decision by Diamond-Star Motors to build a joint Mitsubishi-Chrysler facility in McLean County.

Running for a third term in 1982, Thompson would have a much harder time. The poor economy and the first mid-term election of the Ronald Reagan administration made for a more uphill climb. Thompson’s Democrat opponent was U.S. Senator Adlai Stevenson III, the son of a former governor. But Thompson held on, winning by just 5000 votes in a race that was not able to be definitively called in his favor until the results were formally certified three weeks after Election Day.

At the outset of his third term, Thompson proposed a tax increase of close to $2 billion, with hikes on gasoline and liquor as well as income taxes. The resulting deal saw some of those increases enacted along with a temporary income tax increase. Another deal led to higher gasoline taxes and more state funding for mass transit in Chicago and highway maintenance downstate. Some increases in education funding also followed.

Thompson was not as successful after he was re-elected in 1986, this time by a much more comfortable margin. Thompson was forced to veto more than $300 million from the state budget, portions of which were upheld by the legislature in the fall. In 1989 Thompson signed legislation enacting a temporary tax increase for education and local government. This increase was later made permanent.

During this time, Thompson launched a major development program called Build Illinois. Funded by bonds, Build Illinois led to $2 billion in new capital construction across the state, the centerpiece of which was the Illinois State Library across the street from the Capitol building in Springfield. The program created needed jobs, but left the state with more debt to be repaid over many years.

It was also during his fourth term that Thompson achieved another of his most successful agreements: the vote in the closing hours of the 1988 spring session to get the funding for a new stadium for the Chicago White Sox.

The White Sox deal was the culmination of Thompson’s years as an accomplished bipartisan dealmaker in Springfield. In 1980 he convened a summit at the Executive Mansion to address a funding shortfall for Chicago schools. He refused to let participants depart until they had come to an agreement. Thompson negotiated deals between labor and management as well as between the state and the city of Chicago.

Thompson was a fixture in the Springfield community. During his years as Governor he made the Executive Mansion his family’s home. It was his daughter’s first home, and the First Family was often seen around town, just like any other Springfield resident. He helped to open the Illinois State Fair by going down the giant slide in blue jeans. During a protest of controversial legislation, Thompson once set up a beer tent on the Mansion’s lawn and invited protesters to have a drink.

Thompson even held an Antiques Fair every year on the Mansion’s lawn. He was an admirer of the arts, and not only required a small percentage of all public building contracts to be set aside for artwork, but also created the state’s network of artisan shops. Thompson was a friend of historic preservation efforts around the state, creating the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency.

The Thompson years were a period of change in state government. After the legislature enacted a pay raise over Thompson’s veto in 1978, voters amended the state Constitution to cut back the size of the House of Representatives from 177 to 118 members, and to eliminate multi-member districts with minority party representation. In his final year in the office the U.S. Supreme Court issued its ruling in the Rutan case, declaring hiring for state jobs based on party affiliation to be unconstitutional.

Big Jim Thompson left the governor’s office in 1991 after 14 years, retiring as the longest-serving governor in Illinois history.

“He was a hands-on governor who loved the process of getting things done in Springfield, and his accomplishments still stand strong today,” said House Republican Leader Jim Durkin. “Our state was fortunate to have such a dedicated leader.”

Thompson returned to practicing law after his time in office, this time with the firm of Winston and Strawn in Chicago. He was picked by President George W. Bush in 2002 to be one of the members of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, better known as the 9/11 Commission.

He will be remembered as a man who presided over state government during dramatically changing times, a governor who left a legacy of public works projects around the state, and a leader who represented an era when elected officials could put partisanship aside and reach agreements for the good of the people.